Before the term “street photography” gained prominence in the 1950s, the practice of capturing candid moments of urban life was often referred to as “documentary photography” or “social documentary.” This earlier form of photography was characterized by its focus on social issues, everyday life, and the human condition, often highlighting the struggles and realities of the working class and marginalized communities. The origins of documentary photography can be traced back to the late 19th and early 20th centuries, with notable figures such as Jacob Riis and Lewis Hine, who used their cameras to expose the harsh living conditions of the urban poor and child laborers, respectively. Invariably posed, their work laid the groundwork for a movement that sought to document social issues and advocate for reform (Petrovich & Cronley, 2015).

This approach was not merely artistic; it was deeply intertwined with social activism, aiming to raise awareness and provoke change through visual storytelling (Tulumello et al., 2019). As street photography began to evolve, it retained many elements of documentary photography, particularly in its emphasis on candidness and the portrayal of everyday life. Photographers like Henri Cartier-Bresson and Robert Doisneau, who emerged in the mid-20th century, continued this tradition but added a more artistic and spontaneous flair to their work. They captured fleeting moments that conveyed emotion and narrative, often within the bustling context of urban environments (Lee & Park, 2018). This shift marked a transition from strictly documentary purposes to a broader artistic expression, where the street became a canvas for personal interpretation and aesthetic exploration. The term “street photography” itself began to gain traction in the 1950s, coinciding with a burgeoning interest in modernism and the everyday experiences of urban dwellers. This period saw a rise in the appreciation of the street as a dynamic space filled with stories waiting to be told, reflecting the complexities of contemporary life (Hunt, 2014). The work of photographers during this time not only documented the streets but also engaged with the cultural and social changes occurring in post-war society, further solidifying the street’s role as a vital subject in photography. In summary, prior to the widespread adoption of the term “street photography,” the practice was largely encompassed by documentary photography, which focused on social issues and the human experience. As the genre evolved, it embraced a more artistic and spontaneous approach, culminating in the vibrant street photography movement of the 1950s.

The present-day

The term “street” has evolved significantly in more recent time, taking on connotations of edginess and danger, particularly in urban contexts. This transformation can be traced through various sociocultural dynamics, including the experiences of marginalised populations, urban planning, and the representation of street life in media and art.

Historically, the street has been a space where social isolation and danger intersect, particularly for vulnerable groups such as the homeless. Research indicates that individuals experiencing homelessness often navigate their lives in environments characterised by threats and violence, relying on street-based social networks for survival (Petrovich & Cronley, 2015). This perspective highlights the street as a site of struggle, where the harsh realities of urban life manifest in the form of social exclusion and risk. The narratives of these individuals often reflect a sense of edginess associated with the street, as they confront the dangers inherent in their living conditions.

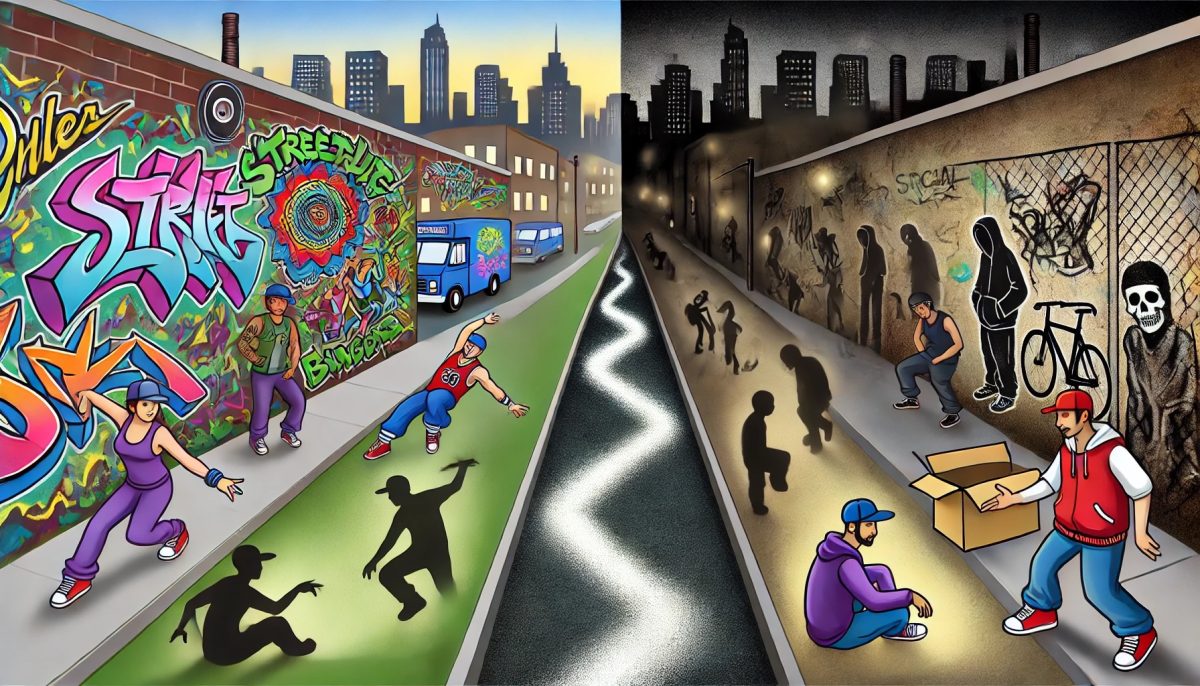

From the 1970s onward, this sense of edginess became more prominent through the rise of urban subcultures, particularly hip-hop, graffiti, and street fashion. Hip-hop culture, which emerged in New York City during the 1970s, symbolised resistance and survival. Street graffiti, often seen as rebellious and illegal, became a visual representation of urban struggles. Over the years, street fashion also embraced the same raw and underground aesthetics, with brands like Supreme and Stüssy drawing from the rebellious ethos of urban life.

This evolving image of the street intertwines with broader socio-political movements, as the street has long been a platform for protest and visibility. The rise of alternative political movements, from civil rights to anti-globalisation protests, has utilised the street as a battleground for social change (Tulumello et al., 2019). The street thus becomes both a place of danger and a site of empowerment for those challenging established norms, amplifying marginalised voices.

The physical design and structure of streets also contribute to this image. Research in urban planning suggests that poorly designed streets foster environments that feel unsafe or chaotic, reinforcing their perception as dangerous (Lee & Park, 2018). Meanwhile, well-designed streets can foster a sense of safety and community engagement. This illustrates how the built environment influences perceptions of the street, which can either strengthen or weaken its association with danger.

In addition, the representation of street life in art and media has played a key role in shaping the cultural image of the street. Urban photography and cultural geography have portrayed the street as both vibrant and fraught with challenges (Hunt, 2014). Through this artistic lens, the street becomes a space that embodies both creativity and risk, cementing its edgy reputation in popular culture.

Thus, the term “street” has taken on its edgy, underground connotations through a confluence of factors, including the lived experiences of marginalised populations, the role of the street in political movements, urban planning, and its portrayal in art and media. Each of these elements contributes to a complex understanding of the street as a space that represents both struggle and resilience.

References

Hunt, M. (2014). Urban Photography/Cultural Geography: Spaces, Objects, Events. Geography Compass, 8(3), 151–168. https://doi.org/10.1111/gec3.12120

Lee, J., & Park, S. (2018). Exploring Neighborhood Unit’s Planning Elements and Configuration Methods in Seoul and Singapore From a Walkability Perspective. Sustainability, 10(4), 988. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10040988

Petrovich, J. C., & Cronley, C. (2015). Deep in the Heart of Texas: A Phenomenological Exploration of Unsheltered Homelessness. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 85(4), 315–323. https://doi.org/10.1037/ort0000043

Tulumello, S., Saija, L., & Inch, A. (2019). Planning Amid Crisis and Austerity: In, Against and Beyond the Contemporary Conjuncture. International Planning Studies, 25(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1080/13563475.2019.1704404