The urban photography movement is an approach in photography. It captures city life, culture, and landscapes. This movement is a branch of street photography. But it goes beyond people on streets. It includes buildings, spaces, signs, and moods. Urban photography explores cities as living systems. Photographers use it to study change, social issues, and identity.

The roots of this movement go back to early street photographers. Artists like Henri Cartier-Bresson and Robert Frank set the stage. They captured candid moments of daily life. But urban photography grew wider. It also captures the shapes, shadows, and textures of cities. It can show the warmth or coldness of urban spaces. Sometimes it can feel abstract. Other times it shows a city’s soul.

Urban photography often shows contrasts. Wealth and poverty, old and new, life and decay appear side by side. It questions urban change. Photographers like Edward Hopper, although a painter, inspired this style. His work showed loneliness in cities. Similarly, photographers such as Saul Leiter captured quiet moments, colours, and reflections. Their photos highlight what we miss when we rush.

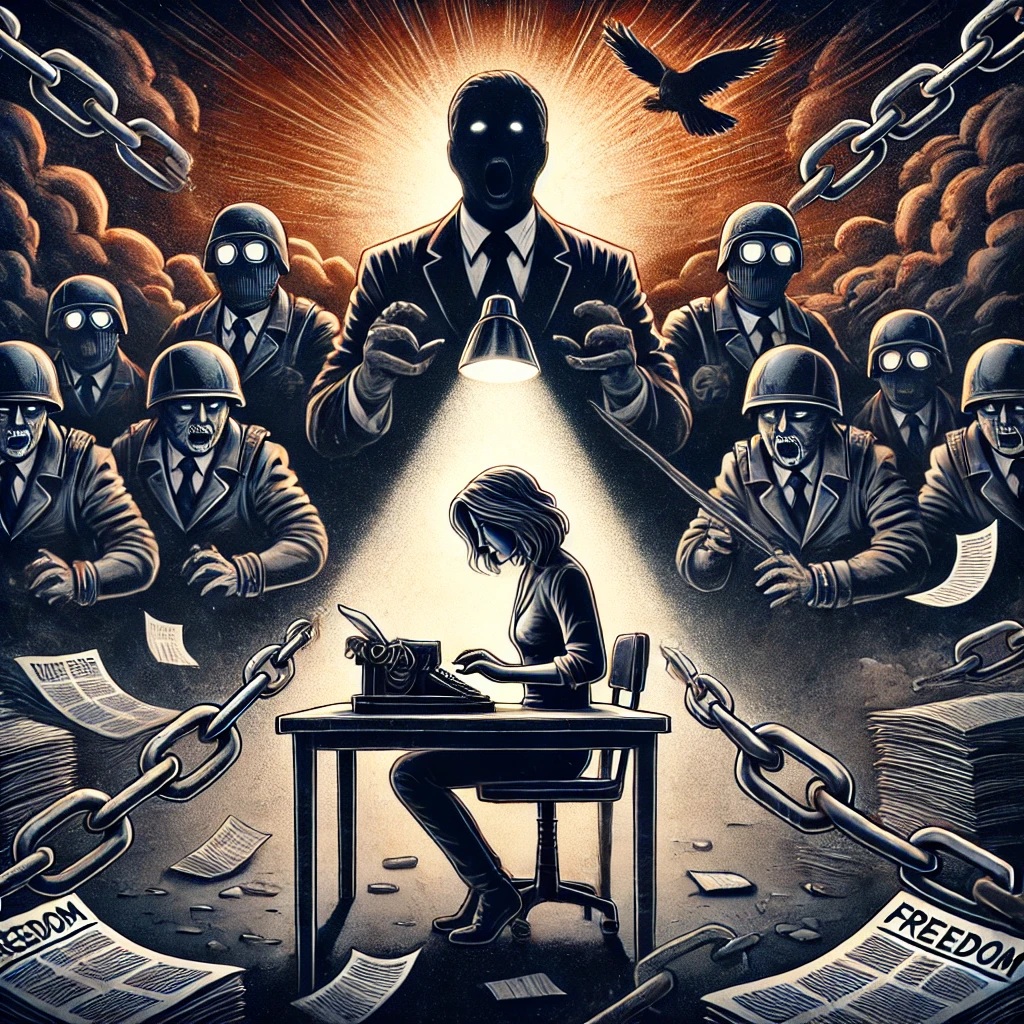

Today, urban photography includes many styles. It can be gritty and raw, showing social issues like homelessness or inequality (Sontag, 1977). It can also be bright, graphic, and clean, showing city design and modern life. Mobile phones and social media made this movement popular. Now, millions of people share images of their urban lives. This movement tells many stories. It makes us think about how cities shape us, and how we shape them.

Urban photography helps us notice the world differently. It teaches us to see beauty in places we might ignore. It also helps us understand complex social issues. By capturing moments, urban photographers help cities speak.

Contemporary examples

Here are some notable photographers who excel in this genre:

Anastasia Samoylova

Based in Miami, Samoylova explores themes of environmentalism and urbanisation. Her series FloodZone portrays Miami’s surreal landscapes, highlighting the city’s vulnerability to climate change. Her work has been exhibited at The Metropolitan Museum of Art and London’s Saatchi Gallery.

Adam Magyar

A Hungarian photographer, Magyar is known for his innovative techniques that blend technology and art. His series Stainless uses high-speed cameras to capture urban life in mesmerising detail, offering a unique perspective on the rhythm of city environments.

Rana El Nemr

An Egyptian visual artist, El Nemr’s work delves into the layered dynamics of urban spaces in Cairo. Her project Giza Threads examines the interplay between dominant structures and fleeting disruptions, revealing the city’s evolving character.

Siegfried Hansen

A German street photographer, Hansen focuses on the graphic elements of urban settings. His keen eye for lines, shapes, and patterns transforms everyday scenes into abstract compositions, highlighting the unnoticed aesthetics of cityscapes.

Marc Vallée

Based in London, Vallée’s photography examines the tension between public and private spaces. His zines document subcultures such as graffiti artists and skateboarders, shedding light on urban youth movements and their interactions with the city environment.

Jason Langer

An American photographer, Langer is renowned for his noir-style images of urban life. His black-and-white photographs capture the moodiness and mystery of cities, often focusing on solitary figures and nighttime scenes.

Dolorès Marat

A French photographer, Marat’s work offers dreamlike interpretations of urban scenes. Using deep blacks and vibrant colours through the Fresson process, her images infuse everyday city moments with a sense of intrigue and timelessness.

References

Sontag, S. (1977). On Photography. Penguin Books.