I’m trying to get my head around what it is that I would be researching if the Morse Experience became my ‘project’. In doing so, I have been revisiting the Research Philosophies area so ineptly covered in MR401. I still cannot see why we were forced to spend so much time exploring this abstract set of concepts particularly at this stage in our research. Twice today I have encountered websites stating emphatically that you MUST understand your research philosophy before you embark on your research. They offer no evidence for this and end up in a tangle of self-contradictory twaddle….

“Research paradigms should be chosen essentially with the research problem and research question or questions in mind…

Paradigms … impact on the nature of the research question… and are a reflection of the value system of the particular researcher. …the chosen paradigm or paradigms have an influence on the data collection methods and research methods that you will use.As a researcher you will inevitably follow at least one of the paradigmatic approaches even if not intentionally. More likely, though, you will position your research at a point where elements of different paradigms are found…

Utilising [sic] more than one research paradigm facilitates the possibility of increasing the comprehensiveness of the knowledge developed through your research. …Some paradigms apply to only one or a limited number of contexts. For this reason the adoption of a number of supporting paradigms might be called for.

You need to choose the paradigm or paradigms early… You will have no basis for choosing the methods or research design that you will follow if you don’t choose your research paradigm or paradigms as an early step, perhaps even the first step after your research problem or hypothesis.

…Research is a circular and recursive process; therefore you may change your paradigmatic approach at a later stage…”

http://www.intgrty.co.za/?s=research+paradigms

It seems singularly naive to suggest that anything MUST be the case in such a wooly field as philosophy, but also to see an evolving research project in such a linear fashion. Of course, those embedded in this particular approach will immediately pigeonhole me as a “pragmatist”.

The definitions of research philosophies are self-referential and therefore circular. “I use a mixture of methods, am aware that some of these are subjective and others objective, but try to reflect this in my analysis, and so I am a pragmatist, because some of my work is subjective and some objective because I have chosen methods that have different qualities.”

Starting with a particular philosophy and sticking to this, inevitably means that only a part of the picture will be revealed, though that might be perfectly OK for a certain situation especially if the researcher is aware of the limitations. However, starting with the ‘event’ and observing it in many different ways is likely to produce a broader understanding though limited in detail.

I remember an incident in my second year of University over 40 years ago. A group of five were arriving at our flat in the Hall of Residence. An early arrival had put labels on our doors – name and subject. Steve, an American student on a scholarship abroad for a year, removed his label explaining that he didn’t like to be categorised.

Rather than trying to establish which box to put a researcher into, perhaps we would be better asking what has led some researchers to want to fit us all into a box in the first place?

At present, the top-down model – identify your philosophy first, then decide on your likely methods, and finally the research question – has taken over the world of research in some institutions. It is put forward by its proponents as the definitive approach – a dogma if ever there was one. It’s time, I believe, that we saw it as such.

There will be some researchers for whom this top-down pigeonholing makes total sense. From my perspective, they are likely to be the ones who have become aware that they lead lives that feel a little out of control, and having a philosophical structure helps them feel less vulnerable. Conversation with them revolves around a torrent of polysyllabic conceptual terms, references to impressive ‘names’, and very little of practical worth. There are others, who do not feel so overwhelmed by complexity, for whom this is not necessary.

It is, in my opinion, time for this dominance to be challenged. Just as I would never have resonated with a career in engineering or theatre or many other fields, I do not resonate with some philosophical approaches. Instead, I led my life as I did (sometimes consciously and often not) evolving my philosophy as I went along. There are plenty of others who would not have wanted my career path and lifestyle. Yes, my particular philosophy of life (and research) has shaped my personal choices throughout.

This doesn’t mean that I wish to impose my own on everyone else, but in my case it does mean that I will resist attempts to impose a view on me.

arse about face (adj)

(1) Placed or arranged the opposite way to the way it should be. (slang)

(2) Arranged in a confused or haphazard way; muddled. (slang)

Different researchers will choose to explore different aspects of a subject. This dictates the kind of data that they are going to collect. They will use methods that suit the aspect that they are exploring. Behind most methods are some assumptions. It can help to understand those assumptions so that you don’t draw conclusions from your data that are biased, distorted or otherwise inaccurate.

| Aspect of interest | Type of information needed | Method(s) of study | The qualities of the research (Axiology) | Underlying philosophy |

| Pure and applied research questions | Highly structured, large samples, measurement, quantitative can also use qualitative | Experiments; surveys | Research is undertaken in a value-free way, the researcher is independent from the data and maintains an objective stance. | Positivism |

| Methods chosen must fit the subject matter, quantitative or qualitative | Case studies; ethnography; narrative inquiry; archival research | Research is laden with values; the researcher, biased by world views, cultural experiences and upbringings, is highly subjective. These affect the research findings. | Realism | |

| Observational and/or Documentary studies with little or no intervention | Small samples, in-depth investigations, qualitative | Case studies; archival research; action research; ethnography; narrative enquiry | Research is value bound, the researcher is part of what is being researched, cannot be separated and so will be subjective. | Interpretivism |

| Mixed or multiple method designs, quantitative and qualitative. | Almost any technique. | Values play a large role in interpreting results, the researcher adopting both objective and subjective points of view. | Pragmatism |

In the majority of situations, a researcher is going to use a number of sources of information in the course of their studies anyway. You would rarely embark on practical research without performing a literature review, for example. You might not refer to it in your dissertation or other published work, but an informal conversation in a pub with a local who knows where to find a particular rocky outcrop, or where the fields are poorly drained, or whatever, is just as much a part of the research – a limited street-based survey with a sample size of one.

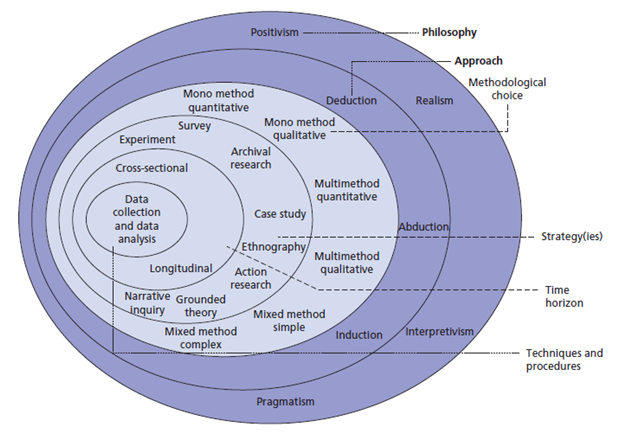

FEATURED IMAGE Source: Saunders, M., Lewis, P. & Thornhill, A. (2012) “Research Methods for Business Students” 6th edition, Pearson Education Limited