Not that many people engage with “practice as research”. Most practitioners are happy simply to immerse themselves in their practice. It is largely a term used in some academic circles.

When I surveyed academics in photography departments for a recent article, most concentrated only on researching the subject matter of their images. If I am going to try to photograph snow leopards in Siberia, it makes sense to know a fair bit about snow leopards and Siberia. Alternatively, and probably as well, I have to hire a ‘fixer’ who knows both. This is not what I mean when I write about research in photography.

The “practice as research” community, being steeped in academia, work differently. The ‘output’ from their research is frequently a retrospective analysis of how their practice has changed over time. They may relate this evolution to psychologically informed journeys, in which case, the calibre of the research depends on the quality of the psychological insights. As most psychotherapeutic authorities would suggest that this is almost impossible to achieve in isolation, and most such theses or monographs are written without such input, the quality is likely to be poor. As the widely held definition of ‘creativity’ is that the output must be ‘widely accepted as novel’ and ‘useful’, this approach, while narcissistically indulgent, isn’t really a contribution to the knowledge bank of the respective discipline.

In recent years, the work of Donald Schön (1983) has experienced a resurgence of interest. He was the first to coin the phrase “reflective practice”. A reflective practitioner working in photography will adopt an iterative approach to their analysis and while it will still explore the underlying psychological journey of the artist, it will apply these insights to their ongoing work. For a variety of reasons, reflective practitioners tend to protect the privacy of their self-discovery – this is not the material of self-promotion but a means of developing the practice, and it is the emergent work that is up for criticism.

Let’s pick a photographic concept and consider different ways of researching it. We are told that the essence of a good photograph is to provoke an emotional response in the subject. I would tentatively suggest that most photographers have the same degree of emotional literacy as the rest of the population – fundamentally illiterate. They might be able to name a handful of emotional terms – some will be emotions; some reactions; some meta-emotions.

A photographer researching this, might spend some time studying the ‘subject’. They would soon discover that emotions are accompanied by physiological reactions, that these can be measured, and that there is a finite list of emotions that do this. They might set themselves the challenge of developing a portfolio of images that demonstrate these.

If they are in the “research as practice without reflection” camp, they will leap in, taking literally thousands of images, processing them and then interpreting how they felt about what they had done.

The reflective practitioner, will also leap in, but they will review how they felt about each ‘session’ and try to learn from this so that their images are getting better over time. The efficiency with which their learning takes place will also depend on the quality of their reflective process, and there is good evidence that this will improve with the help of a good coach, as well as insights from experts in the subject (presumably, here, photographers and ‘psychologists’).

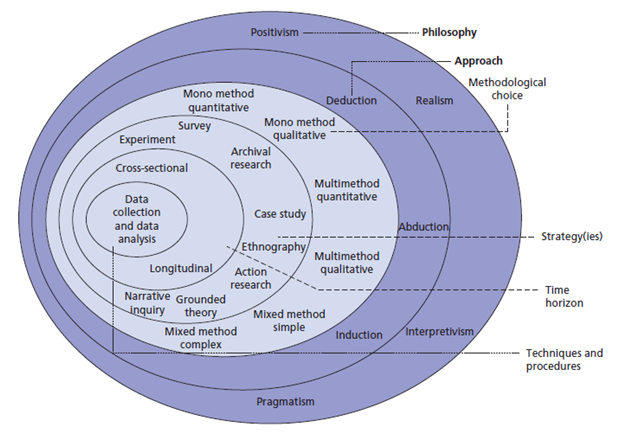

However, there are tools available that accelerate this process, and it is the systematic use of these that moves our hypothetical photographer from being a “reflective practitioner” to a “practice-based researcher”.

Many photographers work in advertising, and so they must surely be familiar with the work of Claude Hopkins. Hired by the advertising agency, Lord and Thomas in 1907, he rose through the organisation to become Chairman before retiring around 1922. His book, Scientific Advertising (Hopkins, 1923) has been a bible for the industry ever since. It was Hopkins who devised a way of testing the effectiveness of advertisements by measuring the response rates of different variants. He would run one advert with one caption and another with a different caption but everything else the same. The coupons used to respond were coded with tiny characters in the corner so that the marketing department of a company could see which prompted most responses and led to most sales.

This is known today as “A/B Testing” and, since 2000, has been the mainstay of internet marketing. The first online A/B tests were carried out by Google that year to determine how many results to display on their search engine pages .

The big difference between Hopkins early work and these User Experience (UX) tests was the development of statistical analysis methods during and after the Second World War. Scientists at Rothamsted Agricultural Research Station were tasked with establishing the optimum conditions in which to grow crops for the British public as they turned over their allotments and gardens to food production (especially domestic potatoes) as part of the “war effort”. They devised efficient ways of designing their experiments and analysing the results and in one season were able to achieve significant improvements. One of the champions of this approach at Rothamsted was a British mathematician, Ronald Fisher.

In the US, at the same time, a telecoms engineer, Walter Shewhart, was developing ways of iteratively improving production processes. He had already come to the attention of an academic, W Edwards Deming, who saw that the systematic approach could be applied to a far wider range of economic problems. After the war, Shewhart would tour India in the company of the great statistician, Mahalanobis, and through this process improved his own ideas.

In the early 1950s, as part of the US-supported recovery of the Japanese economy, W Edwards Deming was given the task of applying these and other approaches to engineers introducing new telecoms systems there. Among his ‘audience’, was an already well recognised young Japanese engineer, Genichi Taguchi. He spent several years working in this sector, refining this approach to provide practical tools that allowed less statistically ‘endowed’ engineers to benefit from quality improvement principles.

In 1954, Taguchi was offered the chance to lecture at the Indian Statistical Institute, and there was introduced to both Shewhart and CS Rao. By then, Rao was in his mid-30s and also seen as a rising star of academic circles, having obtained his PhD in London under Fisher. Rao had developed the Rothamsted models to a more robust form, known as orthogonal arrays, but it was Taguchi who saw that to apply these, the methods needed to be reduced to simple-to-follow recipes. His “Taguchi Methods” became a fundamental part of the Total Quality movement of the 1970s and 1980s and were reintroduced to “western” technologists by, among others, Tony Bendell of Nottingham Trent University.

The internet allowed far larger numbers of trials to be carried out in a short time, and as their techniques improved, so Google accelerated their use – by 2011, they were running over 7000 different A/B Tests alone. In 2012, a Microsoft employee working on the Bing search engine ran their first test of different advertising headlines, just as Hopkins had done 90 years earlier. Today, Microsoft, Google, Facebook, and Mailchimp conduct tens of thousands of these experiments for themselves and their customers each year.

Back to our research-based photographic practitioners wanting to provoke emotional responses in their audience. Equipped with simple tools to measure their physiological responses (pulse rate and skin conductance will be fine), working with a small focus group, they consider a variety of widely recognised images – pooling those that prompt the core eight emotions: ecstasy, admiration, terror, amazement, grief, loathing, rage, and vigilance.

Selecting one of these emotions, and the images that are associated with it, they look for the elements that might be responsible… exposure, lighting, composition, subject, scenario, medium, saturation, white balance, and so on. They identify options for each of these: for example, lighting might be over-, neutral, or under-exposed. They fit them to one of Taguchi’s arrays, and so identify the smallest number of test shots to make. Instead of a long-drawn out process involving many iterations of costly sets, model fees, location hire, etc etc, our researchers can define the combinations precisely. They conduct the shoots and then randomly test the outcomes on a suitably selected representative audience, measuring the physiological responses.

At the conclusion of the work, they have established a definitive set of conditions to provoke each emotion – a significant way of adding value to, and improving the perception of, their work and, if they choose to provide open access to this, then adding value to their profession too.